Frequently Asked Questions:

Bovine Respiratory Disease (BRD)

Understanding The most costly Disease of Cattle Production

Learn from these commonly asked questions how you can build BRD resilience in calves, identify signs of the disease and key considerations as you make treatment decisions.

Causes of BRD

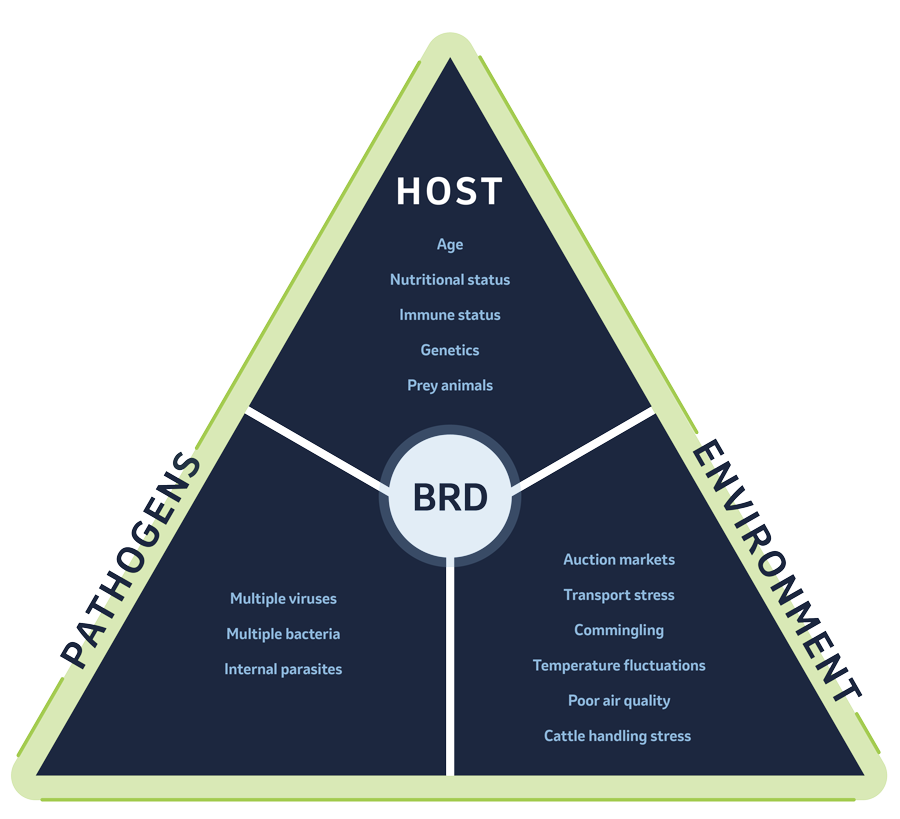

Bovine respiratory disease (BRD), also referred to as pneumonia and shipping fever, is known as a disease complex. It occurs because of interactions between cattle, pathogens, and environmental and management stressors. Several viral and bacterial pathogens are known to cause BRD.

Detecting BRD

BRD is the leading cause of death in beef calves 3 weeks of age to weaning and is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in beef feeding and finishing systems.1 Calves that are lighter weight on arrival or that have gone through stressful events like weaning, transportation, dehorning, commingling, overcrowding and/or inclement weather are most at risk.2

When BRD does occur, early diagnosis and timely treatment are critical to reduce morbidity and mortality, control transmission, and to try to avoid chronic illness. Earlier intervention also offers a greater chance of reducing lung damage that can affect the animal’s future performance.

It is important to recognize signs of BRD as early as possible. This can be challenging because BRD signs can be subtle, especially early in the disease process, and cattle naturally hide signs of disease. Look for:

- Mild depression and lethargy

- Reduced urge to eat or to drink

- Slightly bowed heads

- More frequent nostril cleaning using tongue

Signs of a more advanced disease include:

- Severe depression

- Heavy breathing

- Intermittent cough

- High fever

- Nasal discharge

Presence of these signs, plus a rectal temperature of >103.5 F may indicate a bacterial infection.

SenseHub® Feedlot monitoring technology helps detect animals that are considered outliers to itself and pen mates. It uses an electronic ear tag equipped with sensors to measure ear canal temperature and activity.

Using proven algorithms, if a deviation from the established individual or group baseline norms is detected, an alert is sent to a computer or mobile device. Ear tags on detected animals are illuminated and flashing to make it easier for pen riders to find, sort, and focus efforts on those cattle needing attention.

Preventing BRD

Management practices and health protocols can help young calves get off to a good start and build resilience to BRD. It starts with a good foundation of nutrition, animal handling, and using products and tools to improve cattle health.

Calves are born with a developing but not fully functional immune system. It is possible to begin a foundation of immunity with an intranasal vaccine, such as BOVILIS® NASALGEN® 3-PMH.

BOVILIS® NASALGEN® 3-PMH can be given to nursing calves as young as one week of age. It is the first intranasal vaccine shown effective against both viral and bacterial pneumonia. It is a modified-live vaccine shown effective against five of the major causes of BRD, including IBR, BRSV, PI3, Pasteurella multocida and Mannheimia haemolytica.

As calves get closer to weaning age, a preconditioning program includes vaccinations and management practices to help protect calves against BRD.

A preconditioning program helps boost the immune system and prepare calves for the next stage. It consists of vaccinations, management practices such as deworming and weaning, plus transitioning calves to dry feed. Learn about how to precondition and download a certificate to demonstrate your preconditioning efforts.

To be effective, vaccines must be administered to animals that are healthy and in a condition to respond to the vaccination.

To help select vaccines and get the best results, cattle producers should consult with their veterinarian. It also is important to use proper vaccine handling and storage practices. When you do administer vaccines, take steps to reduce stress and minimize time in the processing facility.

Keep in mind that parasites can impact cattle immunity and their response to vaccines. Don’t forget about parasite treatment, ideally one to two weeks prior to vaccination.

Treating BRD

There are many different classes and types of antibiotics, so best practice is to consult with a veterinarian when selecting an antibiotic to control or treat BRD. They will weigh the pros and cons of different types of antibiotics, including these factors:

- Prior use of an antibiotic and its efficacy.

- The class of antibiotic used.

- The severity of disease.

- The animal’s temperature.

They may also prescribe a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) to help reduce fever caused by BRD. Merck Animal Health offers a full lineup of therapeutic options.

A fever and inflammation are a natural and important response at the beginning of an infection because they can help limit pathogen growth. However, when lingering too long, they can damage healthy tissue.

A nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) can be given to help reduce fever caused by BRD. RESFLOR GOLD® (florfenicol and flunixin meglumine) combines a powerful antibiotic and a fast-acting NSAID in one dose. BANAMINE® TRANSDERMAL (flunixin transdermal solution) is the only cattle NSAID with a pour-on route of administration.

Beef Quality Assurance (BQA) recommends treatment records include the date, identification of animal(s), drugs used, frequency, duration, dose, route, appropriate meat/milk withdrawal and the person administering it. Work with your veterinarian to determine what BRD metrics are best to track for your operation.

Cattle Producers:

Merck Animal Health is Here to Help

Always work with your local veterinarian who knows your goals and health challenges in your area.

Explore the complete line of Vaccines from Merck Animal Health

Disclaimer

SenseHub Feedlot is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease in animals. For the diagnosis, treatment, cure, or prevention of diseases in animals, you should consult your veterinarian. The accuracy of the data collected and presented through this product is not intended to match that of medical devices or scientific measurement devices.

Important Safety Information

BANAMINE TRANSDERMAL (flunixin transdermal solution): NOT FOR HUMAN USE. KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN. Milk that has been taken during treatment and for 48 hours after treatment must not be used for human consumption. Cattle must not be slaughtered for human consumption within 8 days of the last treatment. Not for use in replacement dairy heifers 20 months of age or older or dry dairy cows; use in these cattle may cause drug residues in milk and/or calves born to these cows or heifers. Not for use in beef and dairy bulls intended for breeding over 1 year of age, beef calves less than 2 months of age, dairy calves, and veal calves. Do not use within 48 hours of expected parturition. Approved only as a single topical dose in cattle. For complete information on Banamine® Transdermal, see accompanying product package insert.

RESFLOR GOLD (Florfenicol and Flunixin Meglumine): Not for use in humans. Keep out of reach of children. Do not use in animals that have shown hypersensitivity to florfenicol or flunixin. Avoid direct contact with skin, eyes and clothing as product contains materials that can be irritating. Animals intended for human consumption must not be slaughtered within 38 days of treatment. This product is not approved for use in female dairy cattle 20 months of age or older, including dry dairy cows. Use in these cattle may cause drug residues in milk and/or in calves born to these cows. A withdrawal period has not been established in pre-ruminating calves. Do not use in calves to be processed for veal. Not for use in animals intended for breeding purposes. See package insert for complete information.

References

1. Smith, DR. Risk factors for bovine respiratory disease in beef cattle. Anim. Health Res. Rev. Dec. 2020. 21(2):149-152.

2. Sanderson, MW, Dargatz, DA, Wagner, BA. Risk factors for initial respiratory disease in United States’ feedlots based on producer-collected daily morbidity counts. Can. Vet. J. April 2008. 49(4):373-8.