Equine Health Library

Foal

Wellness & Prevention

Parasitology | Nutrition | Dental Care | Hoof Care

Newborn foals are at risk for a variety of conditions associated with abnormal events during late pregnancy, delivery and/or the first few weeks of life. Examples of potentially life-threatening conditions that can arise during the early postpartum period include overwhelming bacterial infection (septicemia), peripartum asphyxia syndrome (dummy foal syndrome, neonatal maladjustment syndrome), prematurity/immaturity and birth trauma (fractured ribs, ruptured bladder).

Older foals aren’t out of the woods. As they explore their environments and encounter other foals and mares, they can be exposed to a variety of viruses, bacteria and parasites that increase the risk for respiratory disease and diarrhea.

You’ll want to have frequent conversations with your veterinarian before breeding and during your foal’s first year. Together, you and your veterinarian can create a healthcare plan customized for your farm.

Parasitology

Parasitology

The major gastrointestinal parasite of concern in the foal is ascarids. Another parasite, Strongyloides westeri, can be passed from dam to foal in the milk.

Any deworming program should include dewormers that are effective against mature parasites and migrating or encysted larvae.

Consult your veterinarian for the most effective deworming schedule for your horses and region.

Recommended guidelines for foal deworming

- Work with your veterinarian to develop a strategic deworming program that incorporates other classes of deworming products at appropriate intervals.

- Use biannual fecal exams in weanlings and yearlings to evaluate the efficacy of your parasite control program. Discuss these results with your veterinarian.

- Use a weight tape to estimate your foal’s weight and to ensure accurate dosing of all dewormer products

- Pick up all manure frequently and dispose of used bedding. The high temperatures generated by composting can kill ascarid eggs

- Older foals on pasture should have creep feed and hay fed in raised containers to decrease the number of parasite eggs ingested when horses graze directly off the ground.

- Consult your veterinarian for the most effective deworming schedule for your area and region.

Recommended deworming schedule for foals

Discuss this sample deworming schedule with your veterinarian in case you need to make adjustments based on your location, your farm, your foal’s parasite burden and the dewormers that are most effective based on fecal examinations.

- 8 to 10 weeks: Treat for ascarids with fenbendazole (PANACUR® (fenbendazole) Paste; use foal dose of 10 mg/kg), oxibendazole or pyrantel.

- 4 to 5 months: Treat for ascarids and small strongyles with pyrantel, or fenbendazole (foal dose or larvicidal five-day dose).

- Beginning around 4 to 6 months of age: Perform fecals to evaluate the efficacy of the last dewormers used to treat ascarids. If checking the efficacy of the dewormer, obtain a fecal egg count just before and 10 to 14 days after deworming. Compare the before and after fecal egg counts to be certain the drugs you are using are still effective. Discuss your treatment options with your veterinarian.

- 6 to 8 months: Treat for ascarids, small and large strongyles, and pinworms with pyrantel, ivermectin or fenbendazole (larvicidal dose).

- 8 to 10 months: Use ivermectin with or without praziquantel, or double-dose pyrantel, to treat for ascarids, small and large strongyles, tapeworms, and pinworms. Praziquantel and double-dose pyrantel are the only drugs effective against tapeworms. Tapeworms seem to prefer warm, humid climates. Discuss with your veterinarian the need to treat for this parasite in your part of the country.

- 12 months and older: Treat for small and large strongyles, ascarids, tapeworms, pinworms and bots with the right drug for the right parasite at the right time.

Important Safety Information

PANACUR PASTE: NOT FOR USE IN HUMANS. KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN. Do not use in horses intended for human consumption.

General principles of foal deworming:

- Treat all youngsters less than 2 years old as a high shedder

- Include at least one larvicidal treatment (e.g., PANACUR® (fenbendazole) Powerpack) for small strongyles and ascarids during the foal’s first year.

Click here for more information

Important Safety Information

PANACUR POWERPACK: NOT FOR USE IN HUMANS. KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN. Do not use in horses intended for human consumption.

Ascarids

Although any worm can affect your foal, the most significant parasites are ascarids, also known as roundworms.

Ascarids prey on the naïve immune systems of horses less than 18 months old and can cause depression, respiratory disease, interrupted growth, diarrhea, constipation and potentially fatal colic.

Immature ascarid larvae migrate through the foal’s liver and lungs. During their migration through the lungs, immature ascarid larvae cause inflammation resulting in low-grade fever, nasal discharge and cough. Persistent lung inflammation may make your foal more susceptible to other bacterial respiratory diseases. Following their several week migration through the lungs, ascarid larvae are coughed up, swallowed and passed into the small intestines where they complete their development and begin laying eggs.

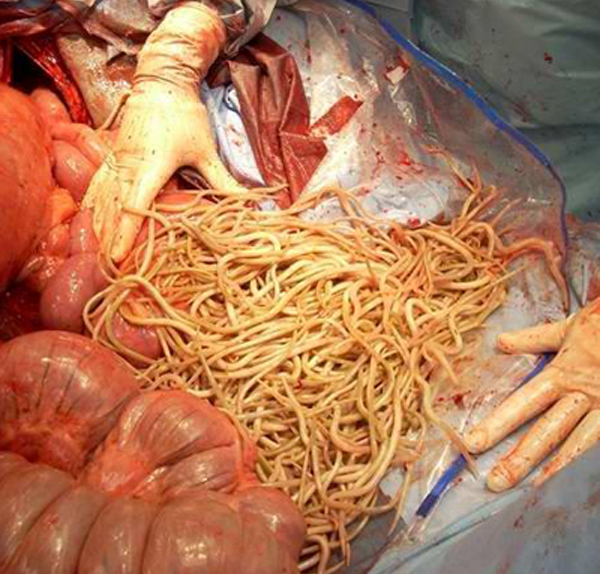

Heavy burdens of developing larvae and adult roundworms in the foal’s small intestine can cause weight loss, unthriftiness and a life-threatening impaction that can result in fatal bowel rupture. As the horse matures into his second year of life, he develops a heightened immune response to ascarids, and the threat greatly diminishes.

Ascarid impaction in a weanling at surgery.

Important facts about ascarids

- Prepatent period is the length of time between ingestion of infective parasite eggs until the adult parasite matures and begins shedding eggs. The prepatent period for ascarids is between 10-15 weeks.

- Female worms are prolific egg layers, and a single female can produce hundreds of thousands of eggs.

- Ascarid eggs are amazingly hardy and can survive on the pasture for eight to 10 years, despite hot temperatures and cold winters. Eggs shed onto the pasture by this year’s foal crop will serve as the source of infection for next year’s foals.

- Febendazole is the drug of choice for ascarid treatment. Pyrantel is also still effective and is a good alternative. Many ascarid populations are developing resistance to the macrocyclic lactone class of dewormers that includes ivermectin and moxidectin.1

To ensure your foal stays healthy, the best procedure is to develop a regular parasite control program that never allows a large population of ascarids to become established within your foal and jeopardize his health while preventing large numbers of adult worms from shedding eggs that will contaminate your pasture for years to come.

1. AAEP Internal Parasite Guidelines (pages 11-12)

Nutrition

Nutrition

Excessive weight gain, unusually rapid growth spurts or a diet unbalanced in calories, protein, calcium, phosphorus, and trace minerals may place your foal at increased risk for metabolic bone disease. Developmental, or metabolic, bone disease includes conditions such as physitis, contracted tendons and defects in bone ossification (e.g., OCD, subchondral bone cysts, Wobbler syndrome).

As your foal grows, he will need a gradual transition from an all-milk diet to solid feed. Typically, creep feed should be introduced slowly within the first month at the rate of 1 pound of creep feed per month of age.

The type of feed offered will depend on the amount and quality of hay and/or pasture in the diet but should be designed to meet the nutritional needs of suckling foals. Consult with your veterinarian to develop a balanced nutritional program for your foal.

Orphan foals

If the unthinkable happens and your foal ends up being an orphan, feeding is relatively straightforward since nutrient requirements and feeding regimes are based on the nutrient intake and nursing behavior of healthy foals. Orphan foals usually have a healthy intestinal tract and normal nutrient requirements.

Your choices are: What formula to use, how much to feed, how often and how to administer it.

Orphan foals fare best if they can bond to a nurse mare. This situation ensures the most physiologic diet and nursing regimen and allows the orphan to maintain normal social and dietary behavior patterns.

Bucket-raised orphans who are deprived of a four-legged role model tend to exhibit delayed ingestion of solid feeds including hay, grass and creep feed. Orphans raised in isolation do not exhibit normal coprophagy (eating their mom’s manure, which is a normal behavior that helps populate the foal’s gut with beneficial bacteria) and miss the opportunity to interact with other foals. If a nurse mare is not an option, then a quiet equine chaperone – such as a gentle pony or retired broodmare – will work. Another viable option is raising several orphans together.

Because orphans are often fed milk replacers and cannot nurse free choice like other foals, they are more prone to gastrointestinal disturbances ranging from constipation to diarrhea. Growth spurts should be controlled to reduce the risk of developmental orthopedic disease (DOD).

Milk Replacers

Fresh mare’s milk fed straight from the udder is ideal. A nurse mare is the perfect solution – a source for an all-milk diet available on demand and a role model and protector for the foal. Discuss this option with your veterinarian.

If a nurse mare is not available, then bucket feeding is the next best option. Popular formulas include mare’s milk, goat’s milk and artificial replacers formulated for foals. Recent studies show that mare’s milk is the preferred diet for a foal in terms of digestible energy and nutrients. Goat’s milk is higher in fat, total solids and gross energy than mare’s milk, but it also is more digestible than cow’s milk due to its simpler fatty acids, smaller fat globules and better buffering capacity. Cow’s milk is not a suitable substitute.

A variety of commercially available mare’s milk replacers also are available. The ideal replacer should closely match the energy density of mare’s milk (approximately 0.5 kcal/ml as fed) and should contain 23 percent crude protein, 15 percent crude fat, 59 percent sugar and less than 0.5 percent fiber on a dry matter basis.

How to feed

You can feed your foal through a bottle or a bucket. Bottle feeding is not a long-term option and is the least desirable because these foals often bond too closely with their human surrogates and are slow to develop normal social behaviors. Without a four-legged role model, many orphans are slow to learn to eat creep feed and to graze. They cannot be left unattended outside.

Feeding milk replacer in a bucket is better than bottle feeding. If a foal has learned to nurse from the bottle, it may take some time to teach it to drink from a bucket. Sometimes placing only the nipple in a shallow bowl of milk will entice the foal to use the nipple as a straw and suck milk from the bowl. Eventually the foal will begin drinking without the nipple.

On-demand feeding is ideal but often impractical. Foals less than seven days of age should be fed a minimum of every two hours. If the foal’s gut function is normal, then at least 10 percent of its body weight in milk can be fed during a 24-hour period. If mare’s milk must be reheated, use a bottle warmer rather than a microwave to prevent over cooking, uneven heating and the destruction of normal bacteria that would be acquired naturally by the foal while nursing from the udder. When using milk replacer, it’s important that it is mixed the same way each time to avoid wide variations in concentration. Discard any unused formula.

Begin offering the foal a minimum of 10 percent of its body weight in milk daily divided into multiple feedings. A 50-kg (110 pound) foal would receive approximately 5L (150 ounces) of milk daily divided into 416 ml (12.5 ounce) feeds every two hours. If the foal tolerates that diet, then the milk volume can be doubled over the next few days. Make all dietary changes slowly. Allow orphans access to manure from healthy, recently dewormed broodmares so that they can engage in coprophagy (eating manure) like foals living with their dams.

Nutrition from 2 Weeks to Weaning

By the time your foal is 4 to 6 weeks of age, you can start providing appropriate creep feed. You can feed your foal individually (preferred) or add to your mare’s feed if they are fed together. Divide the feed into two to three meals per day, and feed no more than a 0.5 pound of feed per 100 pounds of body weight in one meal.

When your foal reaches about 2 months of age, his nutrient requirements for growth exceed that provided by the mare’s milk alone. This is why proper creep feeding at this time is important to sustaining optimal, steady growth and development of the foal.

To choose a creep feed, look for one designed and labeled for use by suckling foals. The feed should contain a source of quality protein (usually 14 to 16 percent crude protein in order to provide adequate essential amino acids, including lysine, for growth); a source of digestible energy; and adequate amounts of minerals, including calcium, phosphorus, copper, zinc and selenium; and vitamins.

Adjust the feed intake to maintain a body condition score of 5. Overweight foals, or those that experience rapid growth spurts, may be at an increased risk for developmental orthopedic diseases that include physitis, contracted tendons, club feet, osteochondrosis (OCD), acquired flexural deformities and cuboidal bone malformation.

Of course, you should always provide access to fresh water and good quality pasture and/or hay. Offer a daily minimum of 1 pound of hay per 100 pounds of body weight for 300-to-400-pound foals.

Weanlings

Once your foal is weaned, his ideal body condition score is 5 to 6. Monitor your foal’s body condition frequently and adjust the diet accordingly.

For foals that weigh between 500 and 1,000 pounds, offer a minimum of 1.2 pounds of hay per 100 pounds of body weight daily. Due to limitation in a young horse’s digestive capacity and ability to digest roughage, a maximum of two pounds of hay per 100 pounds of body weight is recommended.

Weanlings to yearlings often have a larger abdomen or “hay belly” appearance because they aren’t as effective at digesting hay or pasture as a mature horse. The larger abdomen shouldn’t be considered when evaluating body condition; follow the score chart to evaluate the body condition of young horses. Horses in this age group must have nutrition provided in a well-balanced, high-quality concentrate feed and not rely on hay or pasture to provide adequate protein, vitamins and minerals to support optimal growth and development.

Balance your weanling’s daily calorie intake with proper levels of protein, vitamins and minerals to support sound growth and development. Too many calories – or adequate calories combined with inadequate nutrient levels – may increase the risk of developmental orthopedic diseases (DOD). DOD is a multi-factorial condition affected by environment, genetics and nutrition. Proper nutrition can reduce the incidence and severity of these disorders but cannot always override environmental or genetic factors.

If you have concerns about your weanling’s growth or nutrition, please contact your veterinarian and/or equine nutritionist.

Dental Care

Dental Care

The initial physical will include an oral exam to look for any congenital defects, including an over-shot or under-shot jaw as well as a cleft palate.

Timing for eruption of teeth

- First deciduous incisors (centrals) present at birth or by 1 week of age

- First, second and third deciduous premolars erupt by 2 weeks of age

- Second deciduous incisors (intermediates) erupt at 4 to 6 weeks of age

- Wolf teeth (first permanent premolars) erupt at 5 to 6 months of age

- Third deciduous incisors (corners) erupt at 6 to 9 months of age

- First molars (fourth cheek teeth) erupt between 9 and 12 months of age

Click this link to view and download the Equine Health Library Foal Dental Records.

Hoof Care

Hoof Care

You also need to pay close attention to your foal’s feet as thrush, cracks and club feet can all be problems. Teach your foal to pick up his feet at an early age. It will make your farrier’s job that much easier as your foal gets older.

Farrier timing

- 2 days to 2 weeks: Have your farrier come out for the first visit and work with your veterinarian to address mild angular fetlock deformities with corrective trimming and shoeing.

- 2 weeks to 2 months: Persistent fetlock deformities require surgical correction before two months of age. Involve your veterinarian early on

- 2 months to 4 months: Begin routine foot trimming as needed